In The Holdovers, Alexander Payne returns to high school to deliver a subtle ode to justice, beauty, and the good.

Payne digs his satiric canines into the casual cruelties of the rich and entitled, the inherent emptiness of boarding school life, and the old-money world that feeds both.

Growing up in Omaha, one is acquainted with only a rarefied few who attended boarding school. For those raised in the Northeast, boarding school is as common as a lawn jockey on a manicured estate. For wild Irish Catholics like The Crotty and precious sons of Greek Orthodox parents like Alexander Payne, boarding schools hold an austere allure, made doubly so by elegant novelists like John le Carré (Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy), who ties the tortured moral sensibilities of Britain’s MI6 elite to what happens to unformed minds at “school.”

From St. Paul’s to Exeter to Choate, the British boarding school long ago crossed the ocean blue. In the immediate aftermath of WWII, it still carried its patrician founding DNA in which ethnic and religious minorities were “visitors—as Damon says to Pesci in DeNiro’s The Good Shepherd, an underrated take on Skull and Bones and the founding of the CIA—to a land divinely run by White Anglo Saxon Protestants. In today’s world of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), all-male boarding schools are a verboten relic of an era in which these bastions of classical enculteration were networking hubs for budding masters of the universe and, if luck held, keepers of western civilization’s flickering flame.

For all their “progressive” attributes, today’s boarding schools are more like incubators of civilization’s leveling and decline. Though still dependent on the beneficence of wealthy connected donors, boarding schools in our globalized era have become places to park inconvenient offspring of Russian oligarchs, Saudi princes, and Chinese plutocrats, as I learned first-hand when I was invited to a northeast boarding school to deliver a poorly received talk on the road less traveled.

Alexander Payne’s The Holdovers is ostensibly about four misfits stuck at a Boston-area boys’ boarding school––Barton Academy subbing for the likes of Andover––over Christmas break. It captures the boarding school at a tipping point, as its grip on young minds competes with the 60’s and 70’s counterculture and the ominous presence of a ghastly war in Vietnam, especially for dropouts shuffled off to military academy by parents disinterested in actual parenting. As teased out at a Halloween night screening at the Jacob Burns Film Center in Pleasantville, New York––in a magisterial Q and A led by long-time New York Times film and literary critic Janet Maslin––Payne meticulously curates a subdued early 70’s milieu, right down to the font in the movie title, the way credits roll, and where the R rating is placed. From the start, it’s clear this is not only a film about the early 1970’s but a film about films of that era shot with cameras from the era. A time when Mr. Payne (Citizen Ruth, Nebraska, and his self-admitted masterwork, Sideways) wandered off from his Buffett-approximate home to watch cinema with strangers in the dark at nearby Dundee Theatre (now part of Film Streams, Omaha’s Burns-equivalent, where Payne is a board member).

As a primary school alum of Omaha’s Brownell Talbot––which still evokes a bucolic East Coast boarding school vibe––and high school graduate of the all-male, Jesuit-run, Omaha Creighton Prep, where Payne and I first met as members of the speech and debate team, the UCLA-trained director had sufficient touchstones to picture boarding school life. This is accented by his friendship with the likes of Omaha City Councilman Brinker Harding––whom Payne slyly name-checks early in the film––a graduate of the Deerfield Academy, where, after rejecting 800 submissions, Payne found his co-star, the Byron-esque Dominec Sessa (Angus Tully).

Deploying this newcomer was a risk given Sessa’s lack of formal training. But Sessa––vaguely Payne-like in his coiffed, capacious, and rakish young male demeanor––possesses the requisite vulnerability to make the story work. Sessa’s turn in Deerfield’s Antigone no doubt provided him the necessary great books chops to grasp the film’s Johnny-style innuendo at play.

But for this angular preppy to be redeemed––Tully is miffed that he does not get to fly to ritzy St. Kitts for the holidays––Payne needs him to display a rich roundness of emotion: tenderness towards a young Asian student who misses home, compassion for the African-American cook (a tender and authentic Da’Vine Joy Randolph) who lost her son in Vietnam, and sadness for the empty life of privilege that leaves him without his biological family over the holidays. A Christmas envelope of cash from Mom, and Dad #2, doesn’t compensate.

Sessa delivers on all levels. Like Election costar Chris Klein, he is the latest “amateur” turned star by the Oscar-winning helmer.

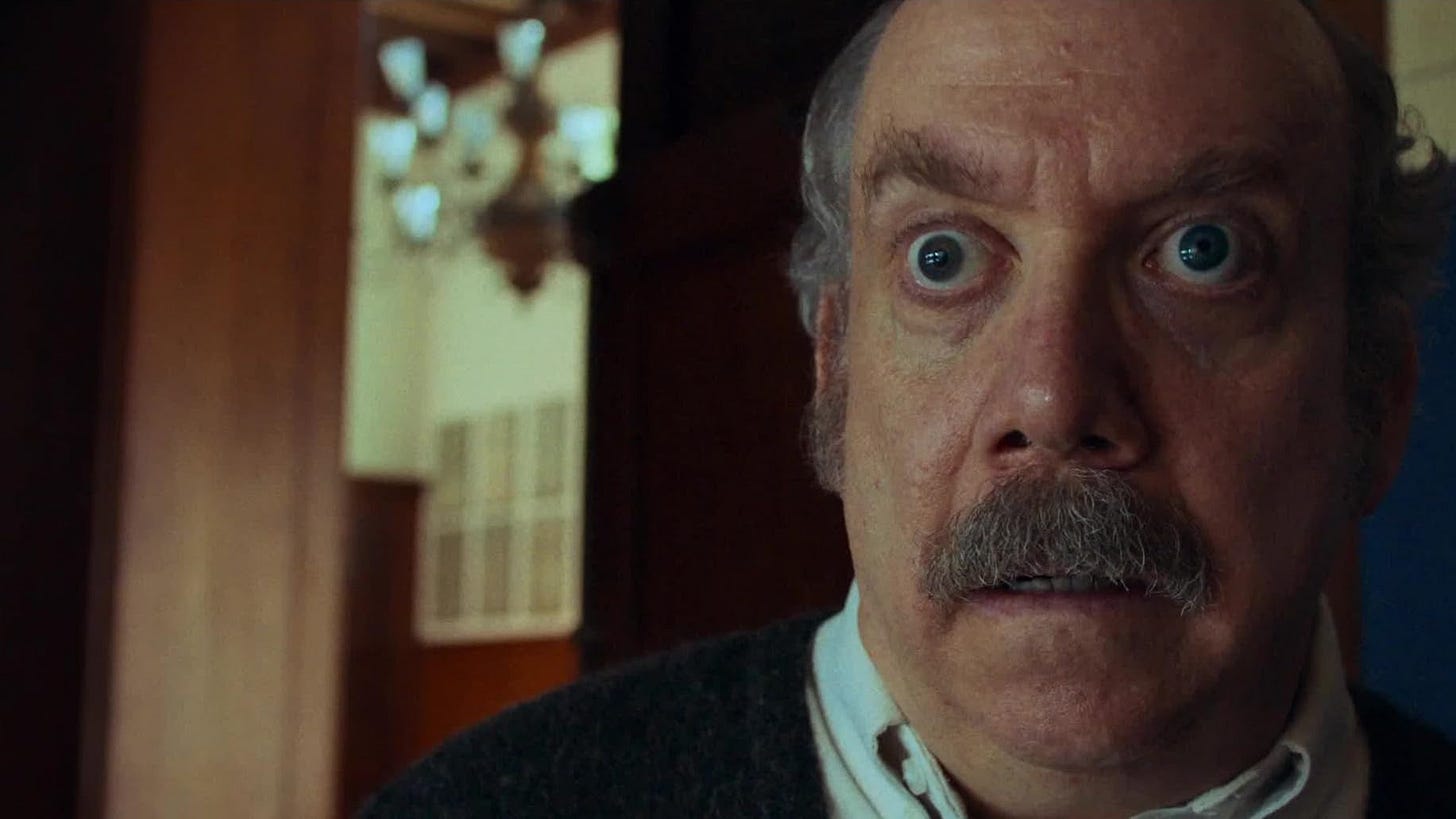

Payne’s merciless and trenchant wit is on full display here, with Paul Giamatti (Paul Hunham) returning as the director’s nebbish mouthpiece and counterpoint to Tully’s seeming entitlement. A master of Chaplin-esque comedic technique––one of Payne’s favorite films is City Lights––Giamatti again plays the sardonic prig to perfection. Except in place of Sideways’ snobbish wine connoisseur, we find a pompous, wryly detached schoolmaster who endlessly quotes Latin and takes pleasure in assigning extra homework over the holiday as he drills Thucydides into the heads of teens who’ll run a country that’s a far cry from the categorical imperatives of Payne’s ancient Greek ancestors. As just one example: instead of giving his fellow holdovers a Christmas gift they might actually enjoy, Hunham gifts them Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations, his bitter retort to the injustices the world has inflicted upon him.

As the jokes flow like water from the icy smart River City auteur, Payne unmasks the sadism, hypocrisy, and inhumanity of boarding school––and ensuing Ivy League–– through the mangled Hunham’s sacrifice at the hands of blue-bloods whose offspring he’s paid to mentor. He is the nomadic “Hun”––easily discarded by the powers that be. By the film’s end, he has again fallen on his sword to protect the powerful––this time so Tully can avoid becoming grist for the Vietnam death mill. Payne does not hold back in delivering his lethal critique of a corrupt, mercenary, and fallen American elite and the dear price one pays to challenge it.

At a climactic moment in almost every Payne dramedy, the director ups the ante of madcap antics to outrageous heights: Giamatti chugging a spit bucket in Sideways, sandal-wearing Clooney racing down the hill in The Descendants, Kathy Bates buck naked in a hot tub in About Schmidt. I was waiting for that hilarious crescendo in The Holdovers, specifically when Hunham makes an impromptu flaming dessert of cherries jubilee on his car hood in the parking lot outside a tony Boston restaurant. But Payne pulls back just when the humor is set to explode. This says something about him at this autumnal moment in his life and career––a high school senior knows and knows that he knows––but also about the seriousness with which he views the human-scaled drama at play.

Payne’s Holdovers are lonely, loveless, and stuck. Payne hermetically cloisters off the era’s political and cultural tumult so they can focus on conquering their flaws and overcoming their sadness as they forge a makeshift family together. While Payne’s resolution is not as crowd-pleasing as in Sideways––in which the nebbish gets the girl––maybe for the 62-year-old sensualist, that sophomoric dream has been replaced by something not exactly political, but, with a nod to Aurelius, pleasingly Stoic.